Share this page

Fermented dairy products

Fermentation is a natural way to keep foods fresh and safe throughout shelf life.

Food preservation has been a key concern since the earliest days of humanity. Among the numerous empirical processes that have been developed and passed down, fermentation is one of the oldest preservation techniques and still widely used in various food matrices.

The fermentation of milk made its consumption possible very early in human history, before 5,500 BC when the ability to digest lactose by adults developed. Milk fermentation by lactic acid bacteria present in the raw milk and within the milk vessels is also the oldest and most gentle method of extending the shelf life of milk.

Fermentation produces beneficial effects in foods that undergo chemical changes caused by microorganisms such as bacteria or yeasts.

Fermentation of dairy is a way of preserving the nutrients found in milk and helping to guard against food waste.

Fermented food products have a longer shelf life and are less prone to spoilage than nonfermented food products of the same matrix.

Advances in the understanding of food microbiology and the ability to screen for microbial food cultures has resulted in the increased ability to stabilize foods by microbial food cultures with bioprotective effects.

Numerous fermented dairy products exist. These include:

- Yogurt: a semi-solid fermented milk product developed as a means of preserving the nutrients in milk.

- Kefir: A cultured, fermented milk drink, similar to yogurt – but thinner in consistency.

- Laban: A fermented milk obtained from lactic acid fermentation of heat-treated milk, which results in acidification and coagulation.

- Lassi: A fermented milk drink blended with water and various fruits.

- Skyr: A cultured dairy product with the consistency of Greek yogurt, but a milder flavor. Skyr can be classified as a fresh sour milk cheese (similar to curd cheese) but is consumed like a yogurt.

- Långfil: Whole milk that is left to ferment at low temperatures with a variety of bacteria from the species Lactococcus lactis and Leuconostoc mesenteroides to produce a fermented milk drink.

The science behind yogurt

For yogurt, milk is fermented at 42 to 45°C by the added lactic acid bacteria Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus.

They form a symbiotic community, supporting each other in their growth. From lactose, lactic acid and aromatic substances are formed. The acidification during fermentation causes the milk to thicken to a gel. Yogurt normally contains at least 10 million per gram viable bacteria of the two species present. Fermentation reduces lactose by one fourth to one third. Together with the lactose hydrolysing enzyme lactase of the viable bacteria, most lactose-intolerant people can easily digest yogurt.

More information: IDF Factsheet on Bio-protection

Learn more about dairy science & technology

The breadth of issues IDF covers in its work is extensive. Find out more about what we do.

Technology behind cheese making

To make cheese, milk is fermented and concentrated by removal of water through the coagulation of th...

Read MoreDehydration of dairy products

Dehydration is an important operation used by many dairy processors to extend the shelf life of milk...

Read MoreThe milk tree – technology and use

The dairy sector processes raw milk into an array of products and by-products, which have a range of...

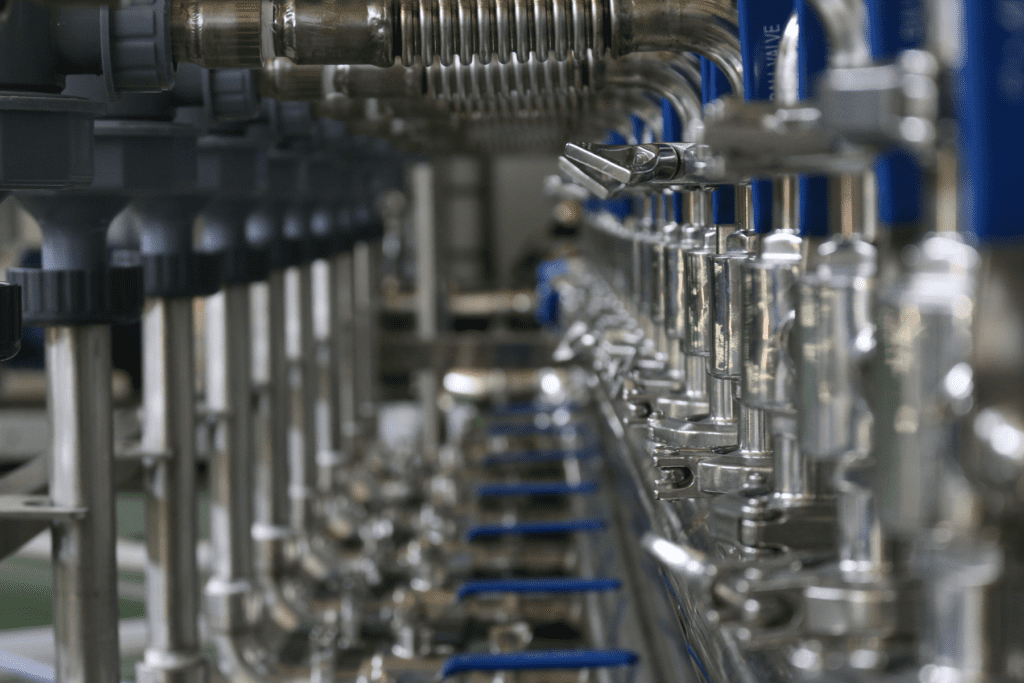

Read MoreDairy focused Membrane Processing

Physically separating and selectively concentrating milk components.

Read MoreRelated reports & publications

IDF provides a permanent source of authoritative scientific and other information on a whole range of topics relevant to the dairy sector.

Related news & insights

IDF provides a permanent source of authoritative scientific and other information on a whole range of topics relevant to the dairy sector.

IDF’s Women in Dairy Science series

On 11 February, the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, International Dairy Federation recognises the extraordinary achievements of....

Enhancing robustness and user friendliness of calculation of TBC conversion relationships

Update of ISO 21187 | IDF 196: A guide to converting the units of routine bacteria analyzers to anchor method units or vice versa is now available ....